Look at your feet and what’s around them in an area roughly six feet square. Study the dust, detail, texture—the parts you usually ignore, the relationships between the various things you see—and you will be halfway to appreciating the life’s work of the Boyle Family. Consider making not only a hyper-photorealist image of that area but a three dimensional model with every nuance immaculately preserved, exactly as is. This is one way to imagine the 11 works currently on display at Luhring Augustine, monuments that are otherwise incomprehensible. It also hints at reasons to make the pilgrimage to witness these disarming works in person: they are the perfect reality check, a counter to the relentless unreality of life during the COVID-19 pandemic.

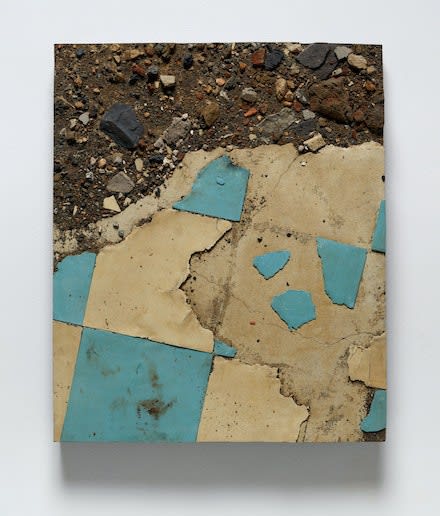

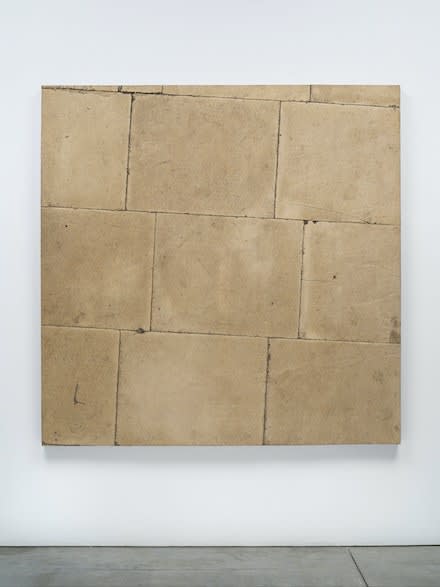

The Boyle Family is a British collaborative group comprised of Mark Boyle (1934–2005), his wife Joan Hills (b. 1931), and their children, Sebastian Boyle (b. 1962) and Georgia Boyle (b. 1963). In their first solo presentation in New York in over 40 years, the Boyle Family’s “earthprobes” are disorienting re-creations of randomly selected areas of the earth’s surface, made from resin, fiberglass, and found materials, that combine Robert Smithson’s earthiest visions with the uncanny eeriness of a Duane Hanson clone. You may wonder how they do it, but they will not say. That would distract from the purpose of their work. The Boyle Family insists that you see life as it really is. Unlike Hanson’s, these works reduplicate physical space. Anyone can ask if a squished soda can is art, but here, surrounded by white walls, something that looks an awful lot like a soda can positioned amidst the rubble of a London street somehow provokes an acute awareness of the here and now in the unsuspecting viewer.

Early on, Boyle and Hills decided to spend their lives working on an art of “everything,” later adjusted to art that “could include anything.” Their “Tidal” series (1969), for example, explores the physical relationships between sand and water. The “Lorrypark” series, created in a truck lot in 1974 West London, reveals a strange spiritual quality never before gleaned from muddy tire tracks. Both of these series, and many others, are represented in Luhring Augustine’s show, and each piece, miraculously transported from its point of origin, uniquely defies understanding while remaining entirely familiar.

Despite the diversity of their subjects, the Boyle Family’s primary objective always remained the same: to teach themselves to see, first making large collages out of rejected material, but soon inviting a thousand blindfolded friends to shoot darts at a giant map of the world—an intention to widen their scope by visiting many randomly selected sites and capturing them. When two thirds of the darts hit ocean or areas that were politically prohibitive, the family began methodically visiting the remaining sites, soon realizing this was more than one lifetime’s work. Their kids officially joined as they visited Australia, Japan, Sardinia, Norway, and the Negev Desert after experimenting with locations in England. Zeroing in with increasing degrees of exactitude on new maps, they eventually sent a carpenter’s right angle spinning into the air to pinpoint each of the final, randomly selected, six by six foot tracts that would become the earthprobes.

In addition to documenting the earth itself, the Boyle Family works with the various organic and inorganic processes and histories accumulated within each random patch of ground. To do this, they collected found objects and live samples, made film and sound recordings of their surroundings, and created microscopic photographs of plant, insect and animal life they found there. They also investigated the repercussions for human beings, using projections of EKGs, bits of skin, or samples of blood and tears in a series of events titled Son et Lumière—for Earth, Air, Fire and Water—for Insects Reptiles and Water Creatures, and finally—for Bodily Fluids and Functions. At these performances, saliva, earwax, semen, urine, and other substances were projected in London underground clubs at the height of the Swingin’ ’60s, attracting both controversy and fame.

As counter-cultural bands like Pink Floyd and Soft Machine played, the influence of the populist scene soon transformed Boyle’s site-related projections into elaborate physical and chemical reaction-inspired psychedelic light shows. As collaborators with their work, Soft Machine brought the Boyle Family along when they toured the United States with the Jimi Hendrix Experience in 1968, giving them important exposure overseas. Despite this, and major exhibitions around the world that have been devoted to their endeavors, the Boyles remain less known here. But by focusing their global awareness on hyper-local surfaces with such painstaking care, they have ensured the relevance of their collective life’s work for all who will experience it.