The courtyard of Somerset House. Strand, London WC2R 1LA

When asked about Black British art in 1988, the curator and historian Eddie Chambers said that its function “was to confront the white establishment for its racism, as much as to address the Black community in its struggle for human equality”. At the time of going to press with my book on the history of Black British art, more than 30 years later, I would assert that work by Black artists still has that function, and the responsibility to assist in that struggle. First, second or third generations of Afro-descended immigrants have used their art-making not only to independently forge their identities, but as an outlet to navigate the experience of “Britishness” that has always been unstable for Black people.

In 1966 the writers John La Rose, Kamau Brathwaite and Andrew Salkey founded the Caribbean Artists Movement (CAM), an interdisciplinary group who sought to promote the work of postwar migrants from British colonies. Active until the early 70s, CAM’s surviving legacy was the activation of a sense of shared Caribbean nationhood outside their home countries, counteracting their reception as unwelcome guests in Britain. These cultural producers exchanged ideas that forged a new Caribbean aesthetic in the arts, setting the stage for a generation of Black artists in Britain to build on.

On Thursday 28 October 1982, the First National Black Art Convention was held, accompanied by a four-week exhibition about “the form, function, and future of black art”. It was facilitated by a group of determined Black art students at Wolverhampton Polytechnic, known as the Wolverhampton Young Black Artists. They then became the Pan-Afrikan Connection, and eventually the BLK Art Group, and were both inspired and promoted by the cultural theorist Stuart Hall. Artists associated with the group included Lubaina Himid, Keith Piper, Sonia Boyce, Maud Sulter, Chambers, Marlene Smith, Donald Rodney, Claudette Johnson, Andrew Hazel, Ian Palmer and Dominic Dawes. Together they went on to be key players in the 80s Black Arts Movement (BAM) in the UK, at a time of social and political upheaval in Thatcherite Britain.

Slowly, and in small doses, some Black artists became more visible over the years: their work was acquired in museum collections, and they transitioned to galleries and auction house showcases. But insufficient comprehension of their work by critics and historians does not encourage any serious or lasting dialogue. In the absence of a relationship with the mainstream art world, Black artists often had to exhibit their work in alternative spaces, not specifically dedicated to contemporary art.

In more recent times, the hugely popular exhibitions Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power (2017), The Place Is Here (2017), and Get Up, Stand Up Now: Generations of Black Creative Pioneers (2019) have galvanised a new audience, generating an overwhelming interest in art by Black artists from the general public, students, institutions and the private art sector. The value and necessity of Black art should, by now, be a moot point, and instead the weight and responsibility should remain on those who ignore Black artists and are reluctant to engage with charged personal histories that are uncomfortable to them.

These overdue advancements aggregate the possibilities and implications of Black British art created in the 20th and 21st centuries. Accessible digital technology, image- and text-based social media platforms such as Twitter and Instagram, and growing creative capital have provided a much-needed revamp to the unwritten rulebook of the largest unregulated market in the world. Our culturally meaningful experiences appear in multiple forms, and visual content and codes migrate from one to another.

Four important Black British artists

Joy Labinjo

Labinjo’s mammoth paintings are depictions of family members or interesting strangers discovered through photographs. This month, Art on the Underground presents 5 More Minutes, a new public commission at Brixton underground station inspired by Black female subjectivity.

Lakwena Maciver

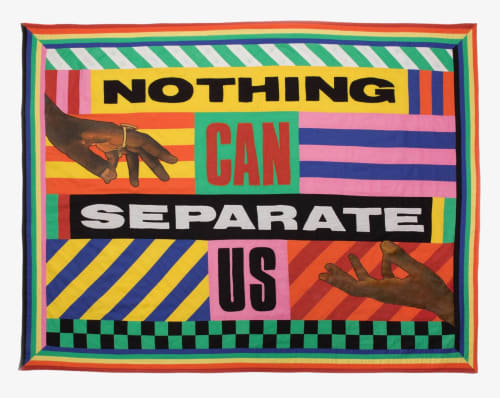

Nothing Can Separate Us (pictured top)

In her domineering graphic design of brightly contrasting shapes and colours, London-based Maciver uses pleas and devotions to command the viewer’s attention. The visual language in her installations is now taking over train stations, public parks and art fairs internationally, stirring joyous and hopeful emotions in the viewer.

Hew Locke

Having spent his formative years in newly independent Guyana, Edinburgh-born Locke is deeply invested in deciphering and repurposing the iconography of the British Crown using metal assemblages and textiles. In March 2020, Tate Britain will reveal Locke’s Britain Commission in the Duveen Galleries, the first public galleries in England designed specifically for the display of sculpture.

Barbara Walker

Birmingham-based Walker has sustained her varied artistic practice since the 1990s but her most striking artworks are large-scale charcoal portraits. She typically draws her local African-Caribbean community on paper except on her 2019 Turner Contemporary residency where she drew her chosen Black female sitters directly on to the walls of the gallery.

Rianna Jade Parker is a critic, curator and researcher. A Brief History of Black British Art is published by Tate on 9 December.