Sport. The final frontier. At least it seems to be as far as art is concerned. For mysterious reasons there is very little important art about sport. In real life it’s a huge and global obsession. In art only a few have boldly gone there.

An exception — an exciting one — is Lakwena Maciver, whose show at the Vigo Gallery made my eyes buzz and whose chief topic is basketball. Her work comes at you like a crossover dribble by Michael Jordan. Everything hits the backboard with a big bang of colour. If art made noises, this event would be clapping, slapping and whooping. But its basketball meanings are not obvious and there’s plenty to ponder here. Which we’ll do once we’ve puzzled over the bigger question of art’s reluctance to engage with sport.

Is it a class thing? Yes, sometimes. It’s certainly significant that one of the few sports to feature recurringly in art is racing. From George Stubbs at Epsom to Degas and Toulouse-Lautrec at Longchamp, the horse-owning classes have usually found someone keen to record their Derby winners.

Boxing has also popped up, notably in the savage batterings of the American punch painter George Bellows, whose pugilism seems always to be witnessing a fight to the death. In his art it’s the human condition that’s being recorded, not the bout itself.

And what about football? When you think how popular it is globally, it’s remarkable how little art there is about it. In the early days of modernism the Italian futurists painted a few soccer players in action, but they were only interested in capturing movement. LS Lowry’s famous Going to the Match, where the crowd of matchstick men converge like iron filings on the Bolton Wanderers ground, is a piece of dank social observation that’s using the occasion to capture a drizzly northern atmosphere.

What these attempts share is an avoidance of the sport itself and an interest in other meanings. It’s as if artists are born with the sports gene missing; as if loving sport and loving art are mutually exclusive passions.

If we plunge back now into the exciting Lakwena Maciver show we encounter the same complications. It’s a show about basketball, but only in a certain way. Indeed, one of the chief reasons it’s as good a show as it is is because it’s using basketball to talk about bigger things.

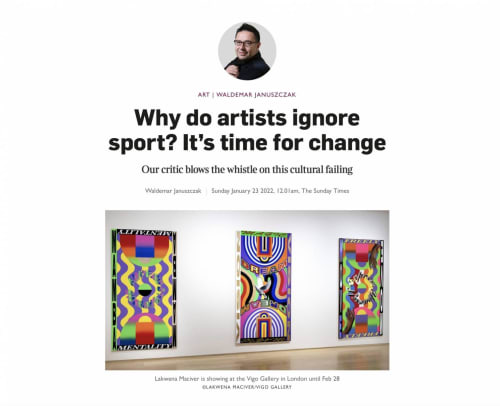

The paintings themselves appear, at first, to be fully abstract. Bright, punchy, zingy, with loud colours and sparkling words. They look like something that might have escaped from a pinball arcade. If sport is being tackled here, it’s not obvious.

The ping moment comes when you notice that each of the paintings has a diagram of a basketball court hidden inside it. You spot it in one image. Then you see it in all of them. Same geometry, although in each instance the courts are decorated differently, as if searching for a different mood.

The next clues are the titles. One picture is called Kobe. Another Magic. A third is Dennis. Now, my sporting passions lie in soccer, where I am that most tragic of stadium creatures, a supporter of Reading FC, but even I have heard of Kobe Bryant, Magic Johnson and Dennis Rodman. They were and are superstars of basketball, players whose greatness is not in doubt.

So this is definitely fans’ art. It turns out that since she painted a basketball court in Pine Bluff, Arkansas, in 2020, Maciver, who’s British, has been an enthusiastic follower of basketball. Her artistic training was in graphic design and those are the skills she unleashes so vividly here in an action-packed sequence of conceptual portraits of basketball’s greats. Using only shapes, colours, glitter and words, she gives each star a particular identity and mood, and evokes each of their specific moods.

Thus the notoriously flamboyant Rodman, who dyed his hair and painted his nails while accumulating seven of the top ten rebound percentage seasons in NBA history, is commemorated in a psychedelic shimmer of reds, yellows and greens around which the words “MOVE FREELY” pinpoint his style and announce his achievements.

Johnson, a basketball superstar of the 1980s widely regarded as the best point guard of all time, was famous for throwing without looking and working with his instincts. “MAGIC VISION” say the words in Maciver’s portrait of him while rainbows of colour form radar patterns around the court like diagrams of his telepathy.

Each of the portraits is the same height as the basketball player they commemorate. So all are tall and thin. All have shiny and perfect surfaces as if the aesthetic of the surfboard has skipped genres. The resulting American feel brings with it the shouts of popcorn sellers and the whoops of delirious cheerleaders.

In the exhibition paperwork Maciver tells us that the Jump Paintings, as she calls them, are also a response to the Black Lives Matter movement. Fabulously active, filled with pictorial agility, they’re trying to capture the beautiful spirit of beautiful bodies in beautiful motion.

However, something else is being recorded here. Something breakable and fragile. Like the wings of a butterfly, the Jump Paintings are also evidence of a season in the sun. They kept making me think: what happens next? Somewhere in the beautiful typography I thought I saw the ghostly words “George Floyd” starting to form.

Art and sport should get together more often.

Lakwena Maciver, Vigo Gallery, London SW1, until Feb 28