Part of an ongoing survey in which artists, curators and cultural commentators explore the question of what African art (of the contemporary flavour) does or can do within various local contexts across the continent.

Ibrahim El-Salahi was born in Omdurman, Sudan, in 1930. His studies in painting at the School of Design at Gordon Memorial College were followed by a scholarship to the Slade in London, after which he returned to teach at the College of Fine and Applied Arts in Khartoum, becoming a leading figure in the movement later known as the Khartoum School. During the 1960s he was closely associated with the multidisciplinary pan-African Mbari Artist and Writers Club based in Ibadan, Nigeria, of which fellow associates included the novelists Wole Soyinka and Chinua Achebe, and the artist Jacob Lawrence. While maintaining an interest in the graphic forms of Sudanese calligraphy, El-Salahi’s work has evolved through a number of distinct phases over the course of his six-decade-long career. At the Slade he had studied European art history going back to the Renaissance, as well as the work of modern masters, but on his return to Sudan, El-Salahi spent a significant period engaging with the natural colours, symbolism and decorative traditions of his home country.

In 1975, while working at the Department of Culture, he was incarcerated for more than six months at Cooper Prison following false accusations of antigovernmental activities. Following his release he left Sudan, living in exile in Qatar and the UK. Between the late 1970s and mid-90s, influenced by his experiences in jail, El-Salahi focused on composite, multipanelled works in black and white, of which perhaps the best known became the monumental nine-panel ink painting The Inevitable (1984–5). Since 1998 he has lived and worked in Oxford, England. El-Salahi’s works form part of notable institutional collections, including those of MoMa, New York; the Smithsonian Institution, Washington; Iwalewa- Haus, Bayreuth; National Gallery of Victoria, Sydney, and the Newcastle Art Gallery, Australia. In 2013 he was the subject of a major retrospective at Tate Modern, the first such dedicated to African Modernism.

ArtReview

Do you think there’s a difference between making art under a democracy and making art under a dictatorship?

Ibrahim El-Salahi

Working in a democracy is a lasting experience; working under a dictatorship is an incentive for doing something – sometimes you can be afraid of the consequences, but sometimes you have to say you have a definite message. There is a large work that I did that is now at the Johnson Museum of Art in Ithaca called The Inevitable and that was a reaction to a political situation. I had to make a statement, particularly as I was working in a safer place outside the country.

AR Did you feel guilty about being in a safer place?

IES No, I wished to be there, because when I came out of jail, I never wanted to leave Sudan at all. I thought of staying until I saw that regime down and out for good, but I had been invited to go to Qatar to help establish the Department of Culture – the same thing that had brought me back to Sudan after working in London as an Assistant Cultural Attache. [at the Sudanese Embassy].

AR What kind of role did art play in society in Sudan then? Was it something that people engaged with, did it have an impact?

IES It took time, particularly as there was no interest from the state in culture. It would only give a sort of lip service, but there was no real interest at all. So the artist is really left alone and trying to create his own public by him or herself continuously. It’s not like in a democracy where there are artistic institutions that help, and you get support from the authorities. That was not created. The difficulty we had when I was asked to set up the Department of Culture (later on subsumed into the Ministry of Culture and Information) in the country was immense. We had to ask for a budget at the end of the year, to cover what was needed to help cultural development in the country. I was only given £2. The main items required were a bicycle and a messenger, but the top man in the country at the time, General Nimeiry, said that because there was a shortage of funds and so on, any ministry should only have 10 percent of its budget. So the budget for the bicycle was supposed to be £20, and they gave us £2. The man in charge of the accounts said, “Culture can give, because now we can buy a bicycle pump!”

AR When you were setting up the Department of Culture in Sudan, did you have to put your own tastes and interests as an artist to one side?

IES I had to stop [making art], because I knew that the job would need work day and night: we had to travel throughout the country to get to the sources of cultural heritage and find out where it was still alive so that it could be built upon. It was a period that was very, very difficult for me and I had to stop work. The same thing happened when I was working at the embassy in London between 1969 and 72: then I also had to stop work, except for a very, very few things. I left no time for myself at all; it was a drab period.

AR Obviously you have a commitment to a kind of public service, is that something you see as the role of art as well? Does the art you make reach out to a public?

IES By necessity. I think it’s wrong for the artist to be put in any situation, but he has to do something other than: ‘What is three plus four?’ But I think if the artist is in some sort of institution that is very well established, then the artist is free to be left on his own to do whatever… For an artist, it’s much better to be left on your own to do your work and then see what happens.

AR When you were painting The Inevitable, what impact did you hope that would have? Is it designed to be an inspiration, to make people aware of something? Can art change the political or social structure?

I believe in the fact that the message from the artist to the public is to let them think and develop their own idea about the work

IES I hope so, because the message I always have is something to start people thinking. I’m not working to give a direct message, but I want the people to absorb it from the work itself. I believe in the fact that the message from the artist to the public is to let them think and develop their own idea about the work. The message that I put in The Inevitable was that someday, sooner or later, people will rise against tyranny, and that is up to them as a group, and they have to have what it takes, what is needed, to work together and to have force enough to make the changes necessary. The message is embodied in the work itself.

AR How much can you as an artist be involved in the actual rising up and the getting together?

IES I think you have limits. As a painter, as an artist, you have to go to a certain point and then leave it.

AR Do you think the role that art plays has changed in Sudan over the last 50 years?

IES I think so. In terms of numbers, in terms of movements, in terms of attitude, in terms of facilities. It’s still very difficult, but relatively speaking there’s quite a lot. Of course now we have artists who are starting their own galleries and then other elements, foreign elements – the French Cultural Centre, American Cultural Centre, the British Council – and they are improving facilities with art exhibitions. Gradually they’re developing.

AR Do you think that those agencies have their own ‘foreign’ agendas?

IES True, because these are people with their own programmes and their own agendas who wish to expand their own nature and influence – using art for a creative link with their own countries. As far as the artist is concerned, it’s a matter of necessity, they have no place to go to except those facilities, and they have to use them. I remember when there were very, very few art students: people preferred to go into other sorts of work – to do engineering, medicine, law and so on. Because people used to say that being an artist was a waste of time. Now large numbers attend the art college. So the awareness about the importance of art in society has been expanded, there are different subjects within it. That tells of the development that has taken place, which is important.

AR Why do you think that development has happened?

IES By sheer necessity and the fact that afterwards they found that art – for instance graphic art – has a marketplace: the calligraphers all studying at art college, they are finding a big market. The fact that it can pay back, that it can give you something to live on, is important.

AR How was it when you were studying?

IES Well, at that time there were very few [students]. The art college started in 1960, the School of Design in 1946. At the time when I joined the college I was in the third batch. Before there were two batches: the first lot was only two students; the second about six or seven. In our time, there were about 16. Now hundreds attend art college. Not only this, but one of our colleagues who was in the first batch to study art in the School of Design, he started his own college, which is far more thriving than the official college – totally different, it’s changing.

AR What sort of things did they teach you?

IES In the School of Design, it used to be painting, drawing, clay modelling, bookbinding, calligraphy, that kind of thing. On the side, a little bit of architecture, but it wasn’t a proper study. Now the college itself has expanded and besides painting has textile design, electronics and computer studies and interior design and so forth. It has expanded itself definitely.

AR How is it for you now that you’re famous and people know your work? Is it harder to work when people have expectations of what your work should be?

IES It is harder, because of all this responsibility, which I try to keep away from as much as possible, but in other words, it becomes inevitable, because people think that I have made it. It’s quite a responsibility, which puts you in a situation where you become very careful about what you say and what you do. And you get criticism, sometimes for or against. I find I’m a kind of a role model for something that I never asked for at all. I get people coming into the studio and writing papers and so on. I go to Sudan usually every year: I go when I have spare time, and I spend about a month or a month-anda- half there. When I come back from Sudan and I start my work, I always tell my wife that I need a holiday. Well after midnight I will have visits from people who are concerned. I appreciate their concern and their appreciation. In my hometown, Omdurman, they did a huge celebration in my honour. I told them, ‘Please don’t do this for me,’ but they had a big celebration. They were happy and proud that one of them has made it outside and become well known and so forth. I think it’s something that is appreciated very much indeed as far as the public are concerned in the country. Not the government: the government, until now, has no interest at all in culture or heritage except as far as it concerns tourism, not aesthetics.

AR What are you working on at the moment?

IES Right now, I’m just thinking. I keep changing continuously, because I don’t want to be put inside a style or a method. The work also changes because my body is changing. Also I don’t want to be caught by what I’ve done in the past. For instance with this so-called School of Khartoum, my relationship was only in the first three years, from 1959 to 62: only that period, then I changed continuously.

AR Do you think art historians like that? Maybe it’s not your choice – it’s not you who gets to decide which box you get put in.

IES Yes, I mean, the box is always there. For art historians and art analysts and people who try to categorise things, it’s much easier, but when they tie you to a certainty [that no longer exists], then that’s a problem. That’s quite a misrepresentation of what you are as yourself, as a whole. You are only linked up as a small part of what you were before and what you left behind. That said of course, I do understand it personally as a whole, and my work, no matter how different it is, is still me, little old me.

AR Yes, and you recognise it? It never seems that an older work might have been made by another person?

IES It has happened to me sometimes, because I used to draw continuously and in a different style. Many times if it’s put in a different light or a portion of it has been shown as a detail, I ask myself, ‘Have I done that really, I don’t remember?’ If it’s the whole thing, then it falls in place – then you know exactly that you’ve done that kind of thing and relate to the body: you’re the same person and the work is only a part of you at that level.

AR What kind of artists inspired you in the early days?

IES I heard about crazy old Van Gogh – this excited me very much indeed – his sunflowers and his brushstrokes. I hadn’t seen it, but I used to hear of it from a friend of mine. He used to study in Egyptian secondary school and they were lucky enough to have someone who was clued up about art and artists and he used to come tell us about it. We lapped it up, excited about the work of an artist who was supposed to be mad and cut off his ear and was in the fields and had those sunflowers. That to me was quite exciting.

AR Yes, was that the idea you had of what it was to be an artist? Do you have to be slightly mad?

IES No, at that time, no, no not particularly. I knew that I was mad already. But I think of it in terms of adding something of a flavour of yourself and your ideas. The other person who I grew very interested in, somebody in the past – pure Renaissance – was Giotto, but mainly because he turned a new leaf from the Gothic art into the beginnings of the Renaissance and to using the third dimension, the raw vision. Others like Alberti, Brunelleschi, the architects who made the visual and theoretical perspective, I got very much interested in them. I went to a course in Italy at that time, way back in 1955, on the background of the Renaissance, which had been run by the British Institute in Florence. That gave me a chance to go tour around all of the school of Giotto. And I find artists like Grünewald quite interesting, because he’s quite individual, he doesn’t follow any school at all. The whole thing is a matter of give and take. Sometimes there are some people whose work you see and you like: it doesn’t mean that you are copying them, but you draw a parallel, you try to bring something of your own. Somehow you relate it to what you have seen and that goes for everything that you see – whether it’s an old artist or a contemporary artist that is interesting and excites our mind – and you do something in response. That’s the kind of thing you could say I’ve been influenced by.

Lately, The Inevitable was shown in Barcelona at the Museum of Picasso. One of the presenters of the TV station asked me, ‘Have you been to inspect Picasso?’ She was quite shocked when I said, ‘No, I haven’t been inside.’ She said, ‘But how?’ I said, ‘Well, actually what you see here is something derived from our own culture,’ it’s the rhythm of calligraphy and African motifs. This is what excited me and why I did that work. It might look to your eye like something related to Picasso, but I assure you it’s not, but it’s up to you if you see it. If you see it as something influenced by Picasso, let it be, because I present the work and my job has been finished, when the work is finished you can interpret it the way you want, it’s a free world.

AR A lot of your own work seems to grow organically…

IES Yes, I work on a new piece, and because I do not know what shape it is going to take, I add pieces. This is something that I learnt in jail. In jail, if someone was found with a pencil or paper, then something terrible would happen. So I used to have smaller sheets of paper and I used to draw small embryo forms. Then I added little bits and I used to bury it in the sand outside the cell, just for fear of solitary confinement for 15 days. Anyway, when I came out, I recalled the same idea of making, and each work [within a group that constituted a larger whole] was framed separately. If you see it as only a particle of a whole, it has the whole in it as well. That kind of thing took me time. After I left jail, it took me 17-and-a-half years – from late 1970s up to the mid-90s – following the same trend, of this idea of the particle and the whole in black and white.

It’s quite different to the European way: having this sketch, then you add things and you take things out of it and so on until it takes a form which this sketch suggested in the beginning. With my work I do not know what form, what shape, what size the work is going to take, and that’s why I start a new piece. Each piece [of the work] has to be framed separately, because it’s an embryo of an idea that I’m not aware of completely. Then when it grows together it creates a whole. This gives to me a relationship between the particle and the whole, between the individual and society, which is upmost in my mind. Until it reaches the whole, which is the human being. So the same thing in the relationship from a religious point of view: you can get the created and the creator.

AR Did you study physics?

IES No, because I know my limits.

AR Ah, but you’ve been talking like someone who did.

IES No, I wish I had, but I didn’t. There is a saying in Arabic: ‘He who works with what he has learnt, God will reward him with knowing what he does not know.’ If you are limiting yourself to what you know and use it to the maximum extent, then you will be rewarded with something else. That is my cup of physics for the future.

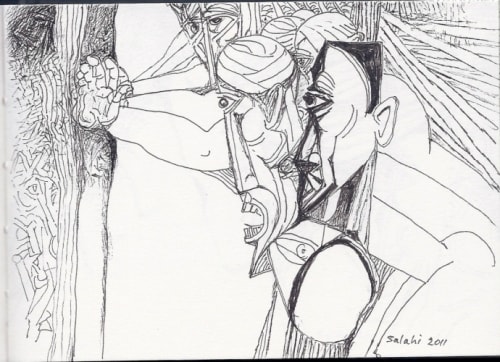

AR During the Arab Spring you created drawings in a notebook. Was that about hope or frustration?

IES That was because I felt held back by the flu, a terrible flu and couldn’t go to the studio, so I worked at home on this small notebook. I wished I was there to celebrate and to give a hand. The only way I could give a hand was just to make drawings and little things, because I couldn’t get out. It was to celebrate the fact that this kind of idol, this kind of tyrant had fallen down, but I was afraid that other people might come and replace them and do the same if not worse.

AR The drawings that you made in the prison, were you able to take them out or did they just stay in the sand?

IES No, I left them in the sand, because when they called your name that means one of four things: either they’re going to send you to another cell within the jail, or they’re going to send you to another jail somewhere else in the country, or they’re going to set you free or they’re going to chop your head off. When they called my name, I just got my things and stood there until they took us to the security and left me and said, ‘Go.’

This article was first published in the April 2015 issue.