Among the most striking examples of the museum's more global and inclusive approach is a gallery with the theme War Within, War Without

This month, the Museum of Modern Art reopened after a $450m expansion with a resolve to embrace the 21st century and provide a fuller, more global narrative in its permanent collection galleries. Mixed in with the white male giants of the Modernist era, from Picasso to Matisse to Pollock, are more women, more African Americans and more artists from Latin America, Africa and Asia.

Rather than labelling all of the galleries with the old, familiar “isms”—Cubism, Surrealism and so on—the museum has come up with some short thematic titles that invite museumgoers to reflect on certain contexts, such as Paris 1920s, From Soup Cans to Flying Saucers and Before and After Tiananmen. In a bold manoeuvre, MoMA has also dismantled the barriers between media by installing films, architecture and design objects, and works on paper amid the paintings and sculptures on view.

Among the most striking examples of this approach is the fourth-floor gallery titled War Within, War Without, where a constellation of works dating from 1965 to 1979 explore themes of violence, personal turmoil and political trauma.

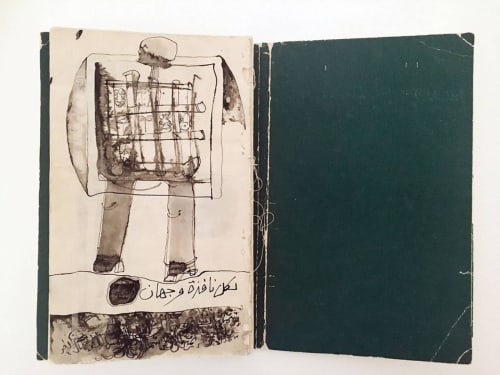

Given pride of place is Prison Notebook (1976) by the Sudanese artist Ibrahim El-Salahi, who was imprisoned in 1975 after being falsely implicated in a failed coup. Eventually released but confined to house arrest, El-Salahi began filling a sketchbook with pen-and-ink drawings and vivid prose and poetry evoking his experience behind bars. “We knew right away we wanted this amazing object at the centre,” says Esther Adler, an associate curator of drawings and prints.

Beyond focusing attention on a part of the world that MoMA has traditionally bypassed, the notebook reframes more familiar works such as Philip Guston’s Deluge II (1975), a prosperous artist’s evocation of catastrophe in a brutal world. That painting in turn expands when juxtaposed with works by artists exposed to that reality in Venezuela (Marisol’s full-body lithograph from 1971), post-war Japan (Tetsumi Kudo’s 1972-73 sculpture) and a divided Korea (Ha Chong-Hyun’s 1974 paint-on-burlap piece).

Punctuating the quiet of the gallery is a 1979 video of Lotty Rosenfeld’s A Mile of Crosses on the Pavement, in which the Chilean artist turned road markings into crosses in a protest against Augusto Pinochet’s military dictatorship in Chile.

Benny Andrews’s Expressionist painting No More Games (1970) meanwhile evokes the plight of African American artists living in far more straitened circumstances than Guston’s. It also points to the fallacy of groupthink in linear art history: though acquired by MoMA in 1971, No More Games has rarely been shown because it did not fit neatly into a narrative of painters eschewing figuration in the 1970s. Viewing it here attests to the museum’s goal to “make more stories visible” in its collection galleries.

Finally, Adrian Piper’s Conceptual series Food for the Spirit (1971), in which the artist photographed herself before a mirror while chanting Kantian texts, drives home the fact that nearly every work in Gallery 420 is a meditation on how human beings cope, and how some find art necessary to their survival. “Artists are not just the sum of their works,” Adler says. “They are people in the world, like all of us.”